My aunt, Tia Connie, decreed by the doctor to live for perhaps six more months, passed on a few days ago-a month after the pronouncement.

My aunt, Tia Connie, decreed by the doctor to live for perhaps six more months, passed on a few days ago-a month after the pronouncement.

It’s true that she had a long life, close to 88 years, on this side of the universe. But it’s also true that 88 years is not long enough for her family.

My mother’s sister, Concha, or Connie as she was known, was her only connection to the ancestors, antepasados , those who came before.

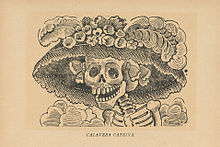

It is like the ancestors held threads in their hands, to the past, present and future. First there was an abundance of bright colored threads, as strong as three ply twine, with numerous threads connecting and lengthening like an Aztec Codice. Because we did not have abuelos, our tio’s and tia’s were our ‘anchor’ threads.

Mom’s parents died when she and her younger sister were children, leaving her eldest sister a mother figure at 14 years of age, her second to oldest brother, of 15 years of age, the father figure. The eldest brother, 17 years old, enlisted in the Army when WW II commenced. All of them gone now. Now only one of those anchor threads remain.

The aloneness reverberates through my mother’s grief. On the afternoon of my aunt’s passing, I went over to my mother’s home to give her the unfortunate news. She tells me she ‘felt’ her sister pass that morning. Mom has been ill for a couple of weeks and wonders, out loud, how long she has left. There is fear in her voice. She says she’s not ready.

Her statements fill me with anxiety. I feel pressure in my stomach, a thumping in my chest. Mom is my only connection to my antepasados now. My biological father is still alive, a couple of years older than my mother, but I have never met him. I don’t have a grip, not even a fleeting touch to that side of my heritage. My hands and heart have always been firmly held in the Alvarado Gutierrez histories that now include several different surnames.

Part of the preparation for my aunt’s funeral has been the gathering of photographs from her own collection and my mothers. My cousins, two granddaughters and I comb through several large sticky paper photo albums.

One of the books has a warning taped to the inside cover: “Don’t take these photos,” signed with the full name of my aunt. My aunt was a homemaker, single mom, working mom, grandmother, great grandmother and great-great grandma. She was simply “Nana” to the subsequent three generations.

Her photographs give a pictorial to her familial codex. Black and white photos from the 1940’-50’s of beautiful young sisters with cousins, friends, husbands and children fill one album, meticulously labeled with names.

Polaroid snapshots, from the 60’s-70’s, mark birthdays, baptisms, and weddings. We travel through decades of fashionable clothing, hairstyles, automobiles, and living room furniture, stopping for family stories along the way. We remark at how young they and we once were-also thinner, and seemingly taller. Memories and laughter fill the air. Antepasados permeate these pictures.

The photo albums from the 80’s onward are dotted with grandchildren, grandnephews, great grand children and numerous school photographs, as she was a ParaEducator for the local elementary school district.

Today my cousins have more funeral planning. I’ll help them write the obituary, order flowers, visit my mother, and then print out the last photograph I took of my mom and her sister two days before she passed on.

We will gather together soon, at a velorio, wake, rosary and Mass in my tia’s honor. We will strengthen the threads of our lives, anchoring our children and children’s children, holding onto our families for what I hope is a very long time.